This week, Japan began releasing treated water into the Pacific Ocean from over 1,000 tanks next to the Fukushima nuclear power plant which was inundated in the tragic 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and subsequent tsunami. This release begins the 30- to 40-year process that , who owns the site, and the Japanese government say is key to fully decommissioning the plant.

The water used to cool the reactors, contaminated by exposure to radioactivity in the plant, has been processed through an advanced filtration system to remove the radioactive elements, but it still contains the radioactive element tritium. To address this, TEPCO is diluting it with seawater by 100 times the volume before release. This plan has earned both support as well as scrutiny and criticism from around the world.

The (IAEA) declared the release "consistent with international safety standards" in July, and Japan has earned the endorsement of the United States. However, this has not allayed deep concerns raised by politicians and citizens in neighboring countries, some environmental activists and scientists, the Chinese government, and citizens of the region where the plant is based. Nations across the Pacific Island region, where the painful memory of damage caused by nuclear testing lives on, remain divided on the issue. And countries around the world are watching closely as are the people of Japan.

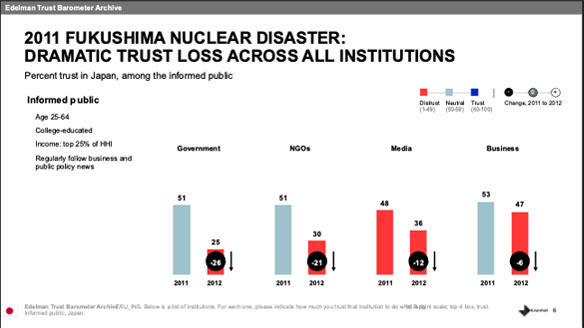

After the 2011 disaster, Japanese trust in their nation’s major institutions collapsed, especially in the government [Reference Chart A]. International New York Times this week quoted Japan resident Azby Brown, “During the 2011 disaster, they (Japanese government) repeatedly minimized the risks, withheld crucial information on the threats to public safety and even resisted using the term core meltdown even though that is what happened.”

Even today, trust levels have still not recovered to pre-2011 levels. [Reference Chart B.] For example, the Japanese government promised to go forward with this week’s release only once it had won the understanding of the local fisheries industry. Yet distrust, misgivings and opposition remain. China’s blanket ban on Japanese marine imports immediately after the release this week reminds citizens of the impact on the Japanese fisheries industry a decade ago. This dynamic is being watched closely by Japanese citizens, a majority of whom think the government’s explanation has been insufficient.

How this critical issue is handled and communicated over the next weeks, months and years will further make or break trust in Japan domestically, in the region and beyond. Initial steps have been taken: Prime Minister Kishida and the Japanese government have worked closely with governments in the region as well as the IAEA, Japan is using AI to combat false information about the water release and TEPCO has a monitoring site to show results publicly in real-time and has already reported their first of daily analysis. These are just a few examples but with an issue this complex that taps into humanity’s deepest fears, more needs to be done.

Now begins the true trust test. Here are three actions Japan can take to rebuild the trust they lost over a decade ago in their major institutions:

- Commit to providing strong information to the community. Trust is local – the only way for Japan to be successful is to be consistent and factual in their reporting of the treated radioactive water release. They must demonstrate a willingness for public accountability.

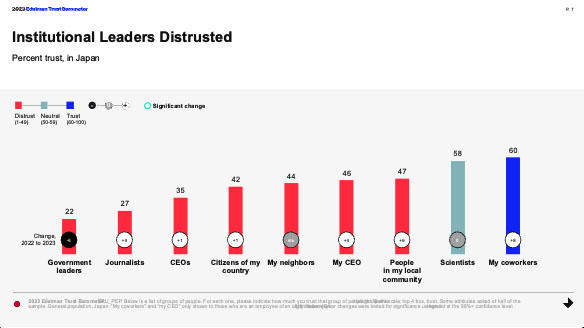

- Engage trusted spokespeople. Though our 2023 ∫⁄¡œ…ÁTrust Barometer shows that all institutional leaders are distrusted in Japan, people in the local community (47%), scientists (58%) and coworkers (60%) are less distrusted than government leaders (22%), journalists (27%), and CEOs (35%).

- Collaborate with a range of independent authorities and amplify their data and voice. This 3rd party endorsement is critical.

Richard ∫⁄¡œ…Áis CEO.

Photo by on